Recently, I travelled to Kenya to visit The Pangolin Project, a PCF grantee working to save the last giant pangolins in Kenya. They are based on the Oloololo Escarpment, a high plateau that overlooks the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya.

As the home of Kenya’s last giant pangolins, it is critical to protect this landscape. Giant pangolins are really special—so beautiful and elusive that conservationists sometimes refer to them as the unicorns of the forest! These gentle giants can weigh up to 70 lbs. and feed almost entirely on ants and termites.

But the pangolins in this landscape are in big trouble—they are facing a number of serious threats and their populations are dwindling. Sadly, The Pangolin Project and Kenya Wildlife Service estimated that only 30-80 individuals currently remain in this area.

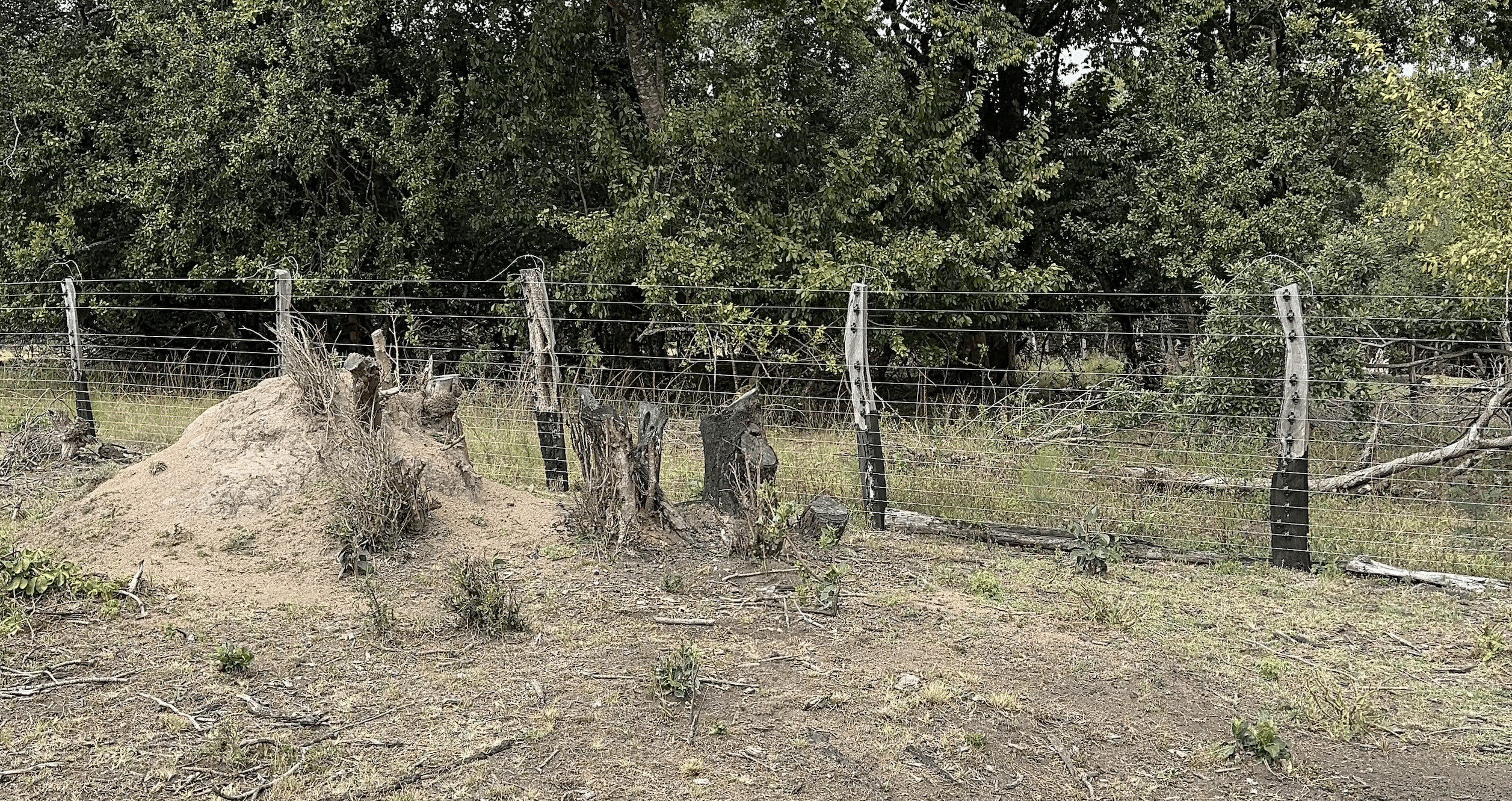

The Oloololo Escarpment is a complex landscape of private landownership, community conservancies, and high-end tourist lodges. Many people protect their plots of land with high voltage electric fencing, and it is this fencing that poses the most immediate threat to giant pangolins.

These fences electrocute and kill pangolins and other small animals, and they also cause land fragmentation for larger species. The Pangolin Project estimates that one or two giant pangolins are killed by these fences each month, and since this species has such a small population and slow breeding rate, electric fences are killing giant pangolins faster than their population can recover.

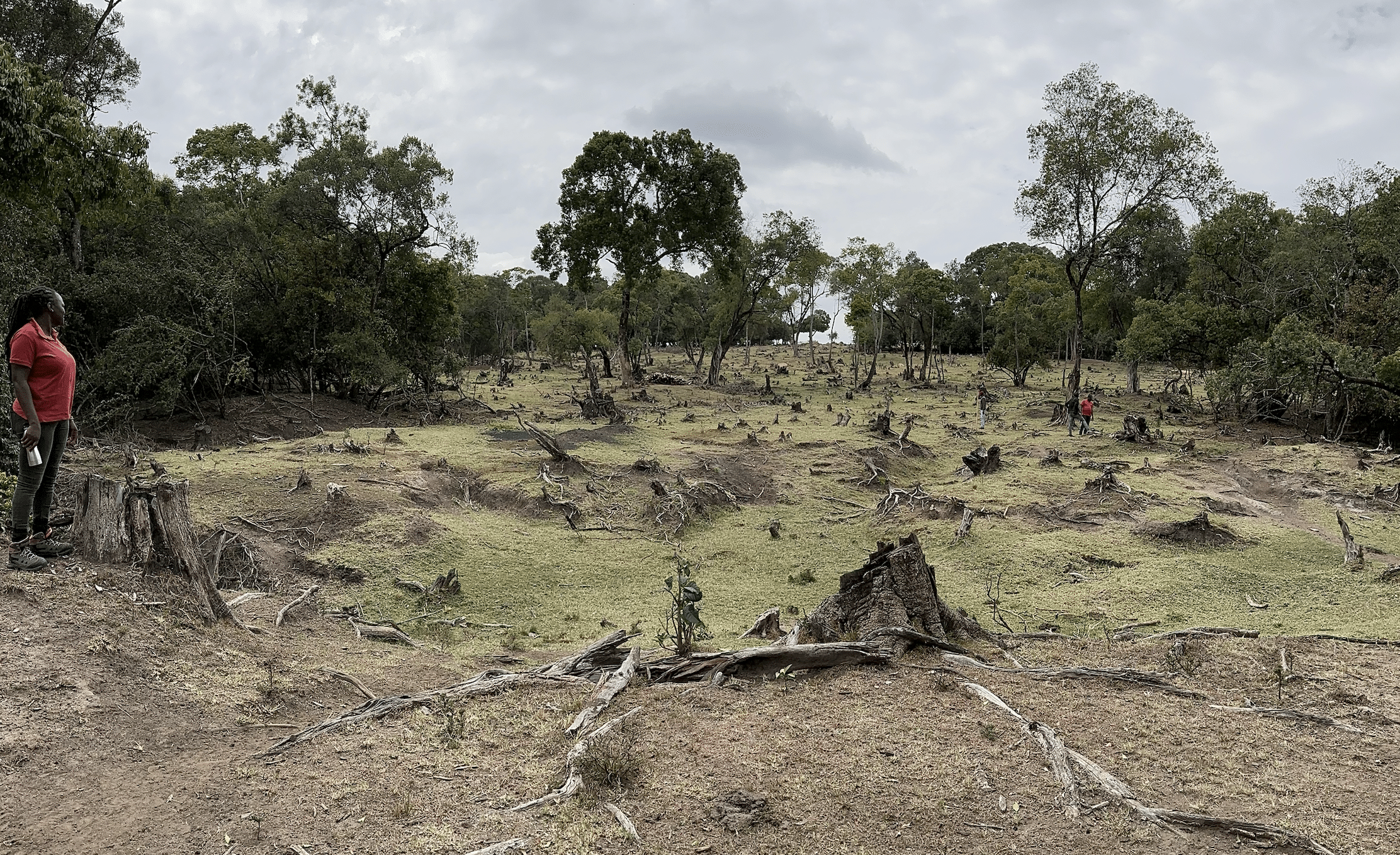

Unfortunately, Kenya’s giant pangolins face other problems too, such as habitat loss. They live in forested areas, but trees are being cut down at breathtaking speed to make charcoal.

Beryl Makori, Programs and Operations Manager for The Pangolin Project, surveyed the impact of logging over the few weeks preceding my visit. She took me to an area that had recently been cleared of most trees, devastating another area of giant pangolin habitat.

As we walked through the area, we smelled smoke from burning charcoal and heard the sound of axes cutting down yet more forest. Landowners clear their land in order to graze livestock and grow crops, which are far more profitable for them than leaving the land undisturbed for conservation.

After all, it is their land. But if giant pangolins are to survive in Kenya, they need some forest to remain intact. This is partly because the ants and termites that they eat live in forest ecosystems. If the forest is lost, the entire ecosystem is destroyed and the pangolins lose a vital food source.

Giant pangolins also need huge burrows to hide from predators and to safely raise their pups, and it’s only possible to dig these burrows in the soft earth of forested landscapes.

Cutting the forest and burning charcoal brings a third problem—poaching. I was told by members of the local community that the Maasai people who live in this area do not traditionally hunt pangolins for food or medicinal use, but the people who are paid to clear trees and burn charcoal are not local to this area. They travel from place to place, meaning they have the opportunity to poach pangolins and sell them to wildlife traffickers as they migrate.

Protecting the giant pangolins that live on the Oloololo Escarpment is incredibly challenging, but as I spent time with The Pangolin Project team and members of the local Maasai community, I understood there is major cause for hope! We have just enough time to save Kenya’s giant pangolins if we support their work. The Pangolin Project has mobilized quickly and put together an impressive conservation plan, working closely with local people to tag and monitor the remaining giant pangolins to help protect them.

Their team attaches tagging devices by drilling a hole through one of the pangolin’s scales. These scales are made of keratin, like our fingernails, so this doesn’t hurt the pangolin at all. Once the device is attached, The Pangolin Project can monitor each pangolin’s movements and help keep them safe.

The Pangolin Project has recruited and trained a team of local Maasai Pangolin Guardians, who travel between villages speaking to people about the importance of protecting giant pangolins and the remaining forest. In less than a year, these Pangolin Guardians have already spoken to 1,800 households, and many of which have been visited up to three times as a result of continued engagement.

The Pangolin Project has also begun working with local landowners to see if they’re willing to remove the lower wires of their electric fences, so that pangolins and other small animals, like tortoises, can pass beneath the fences without being electrocuted. Critically, important local allies such as Peter ole Tompoi, a former wildlife guide and passionate advocate of conservation, have brought community landowners together to create conservation areas. In order to significantly scale up these successful programs, The Pangolin Project needs more funding—and the local community conservation trusts need to be able to generate more income as well.

The Pangolin Project Team are successfully monitoring burrows to see which ones the pangolins are using. They also monitor pangolins through camera traps to better understand how pangolins are using the forest.

Three days after my visit, one of the tagged pangolins gave birth to a pup! Despite all of the threats they are facing, giant pangolins are fighting to survive. This sighting is the first evidence that the population is successfully breeding, and is another important reason why we believe that we can help The Pangolin Project bring this fragile population back from the brink.

The Pangolin Crisis Fund has just approved our second largest grant ever to help The Pangolin Project significantly scale up this important work.